Marian Anderson–Part Two

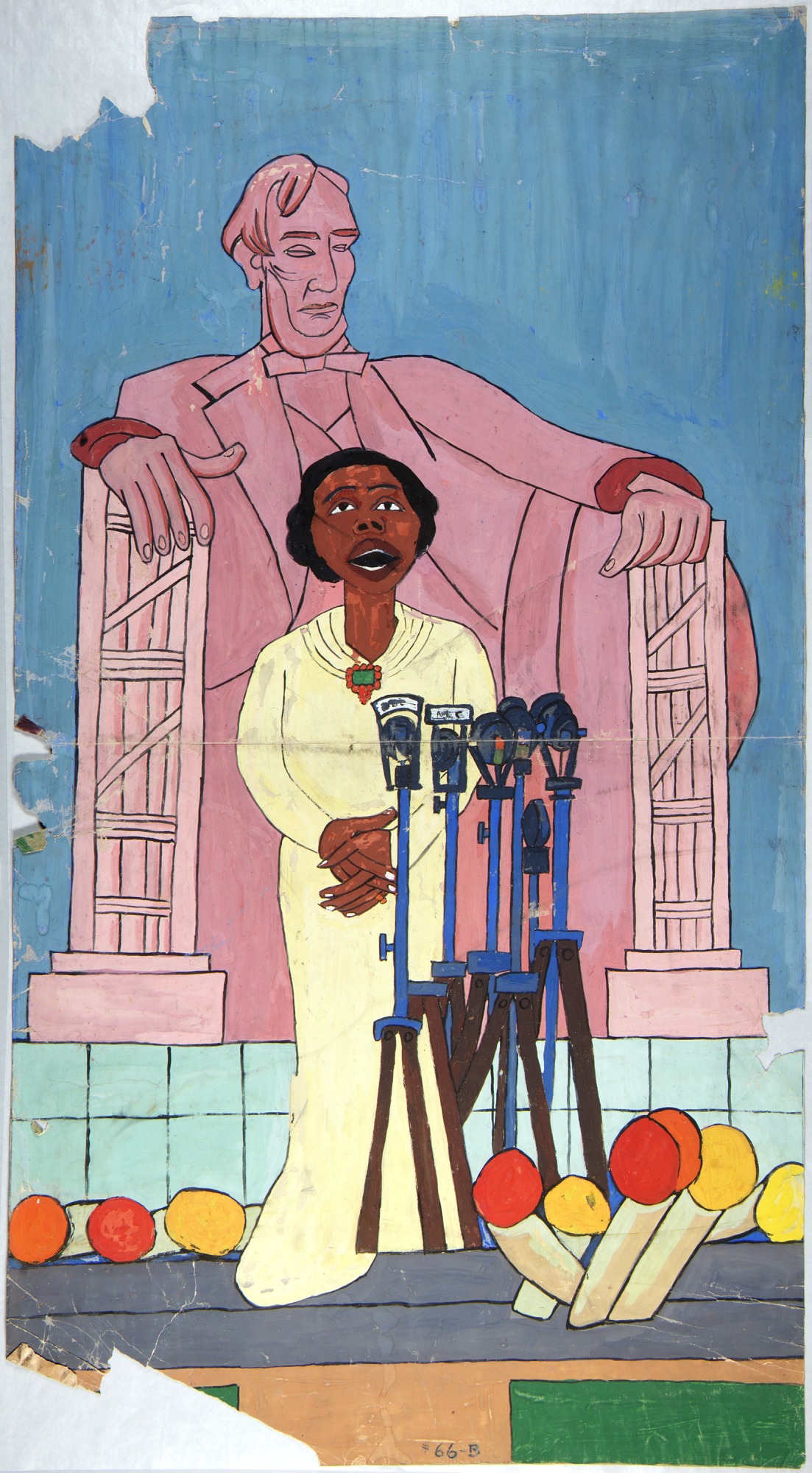

We now come to the difficulties encountered in scheduling a 1939 concert at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., operated by the DAR. After we post this biographical review, we will provide you with a video clip containing a brief explanation of Sol Hurok’s attempt to schedule this concert. However, we need to note that Hurok also tried to schedule the concert at an auditorium of a public high school in DC but was turned down by the District of Columbia Board of Education. A number of civil rights and labor groups created the Marian Anderson Citizens Committee to protest the Board of Education decision. Again, as with the first part of this exploration of Marian Anderson’s career, we are relying heavily on the work of Wikipedia. “As a result of the ensuing furor, thousands of DAR members, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, resigned from the organization.” In her letter of resignation to the DAR, Eleanor said: “I am in complete disagreement with the attitude taken in refusing Constitution Hall to a great artist ... You had an opportunity to lead in an enlightened way and it seems to me that your organization has failed.” Our featured image captures Eleanor Roosevelt talking with Marian Anderson. As we look at this photo, we are struck by a bit of blinding light: both women were courageous advocates for the use of merit and character as the basis for evaluation. However, author Zora Neale Hurston “criticized Eleanor Roosevelt’s public silence about the similar decision by the District of Columbia Board of Education, while the District was under the control of committees of a Democratic Congress…” While Zora’s criticism might be valid, we must remember that Eleanor was not the decision-maker; FDR was the President, and he was a much more timid reformer than his wife. FDR might have been reluctant to take on the issue of desegregation during a period when any Democrat needed the “solid south” in order to win or retain the Presidency. The “solid south” was a euphemism that was best explained by the south’s uniform opposition to equal rights for its black citizens. But the south was not alone in this denial of rights; remember that Princeton, NJ was not in the south. Although Eleanor might have remained silent on political matters, she clearly pushed her husband to persuade Harold Ickes, then Secretary of the Interior, to arrange an open-air concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. While Marian was not inclined to public protests at this point in her life, she is quoted in Spirituality & Practice, as having recognized the need to stay the course in 1939: “I could not run away from the situation. I had become, whether I liked it or not, a symbol, representing my people. I had to appear.” And here is a photo of her standing in front of the statue of Lincoln. In front of Lincoln Memorial

In front of Lincoln Memorial

The great irony here is that, if the DAR thought that the denial of a concert hall would somehow limit the career of a black singer or diminish in some way the power of her voice, they were incredibly short sighted. Their one act of racial bias brought tremendous recognition to Marian Anderson and the quality of her voice. This episode had a profound influence on Marian, in that she understood two things: even if we want to concentrate solely on our careers, we have been helped by many people and we need to do what is right because it is a beacon light to others. Again, here are the relevant quotes from Spirituality & Practice: “I hadn’t set out to change the world in any way, because I knew that I couldn’t. And whatever I am, it is a culmination of the goodwill, the help and understanding of the many people that I have met around the world who have, regardless of anything else, seen me as I am, not trying to be somebody else.” “There are many persons ready to do what is right, because in their hearts they know it is right. But they hesitate, waiting for the other fellow to make the first move — and he, in turn, waits for you. The minute a person whose word means a great deal dares to take the open-hearted and courageous way, many others follow. Not everyone can be turned aside from meanness and hatred, but the great majority of Americans is heading in that direction. I have a great belief in the future of my people and my country.” Two months later at the 30th Conference of the NAACP in Richmond, VA, Eleanor Roosevelt gave a speech on national radio and presented Marian with the 1939 NCAAP Spingham Medal for distinguished achievement by an African American. According to ThoughtCo, Leontyne Price had this to say about the influence that Marian Anderson had on Leontyne’s career: “Dear Marian Anderson, because of you, I am.” Talk about symbolism; in 1965, the same award would be presented to Leontyne Price, the Metropolitan Opera star who had been inspired to sing by the work of Marian Anderson. Here is another ironic aftermath: Marian tirelessly entertained troops during both WWII and the Korean War; and, in 1943, as part of a fund-raiser for the American Red Cross, Marian sang to an integrated audience at the same Constitution Hall. As she said after the fact: “I felt that it was a beautiful concert hall and I was very happy to sing there.” While the DAR might have relented, “By contrast, the District of Columbia Board of Education continued to bar her from using the high school auditorium in the District of Columbia.” They seemed to be part of the George Wallace fraternity of thinkers: “Segregation then; segregation now; segregation forever.” On January 7, 1955, Marian became the first African-American to perform with the Metropolitan Opera, playing the role of Ulrica in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera. The following quote will give you all you ever need to know about Marian’s acute attack of stage fright at the age of 58 and will explain why she chose not to perform in staged operas: “The curtain rose on the second scene and I was there on stage, mixing the witch’s brew. I trembled, and when the audience applauded and applauded before I could sing a note, I felt myself tightening into a knot.” Although she never appeared with the company again after this production, Anderson was named a permanent member of the Metropolitan Opera company. She sang at the Inauguration of Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1957; toured India and the Far East as a Goodwill Ambassador for the State Department and the American National Theater and Academy; was appointed US delegate to the UN Human Right Committee; was elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; sang at the Inauguration of President John F. Kennedy; sang at the 1963 March on Washington; and won the Presidential Medal of Freedom in the very same year. In her final international tour, she finished her tour at Carnegie Hall on April 18, 1965; and with that, at age 68, she retired from singing publicly. The awards, however, didn’t stop: 1973—The University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit; 1977—the United Nations Peace Prize; New York City’s Handel Medallion; Congressional Gold Medal 1978—Kennedy Center Honors 1981—George Peabody Medal 1984—Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award, City of New York 1986—National Medal of Arts 1991—Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award The woman who was refused admission to the Philadelphia Music Academy eventually was granted honorary doctoral degrees from Howard University, Temple University and Smith College. Here is the way Spirituality & Practice summed up her contribution to our country: “Marian Anderson did not originally set out to be a guiding light in the fight for equality; she simply followed her conscience and her passion. Here’s her view of the role that emerged for her: ‘Certainly I have my feelings about conditions that affect my people. But it is not right for me to try to mimic somebody who writes, or who speaks. That is their forte. I think first of music and of being there where music is, and of music being where I am. What I had was singing, and if my career has been of some consequence, then that’s my contribution.’ And what a contribution she left behind. One last note; you may have to go to our website to see the images of Marian Anderson.

Member discussion